There might be affiliate links on this page, which means we get a small commission of anything you buy. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Please do your own research before making any online purchase.

Think about the last time you were in a difficult situation, the kind of situation that requires prompt action.

Something like a tough decision you couldn’t postpone, a heated argument with someone, a sudden and unexpected change, or even a life-and-death event where you had to act fast.

It’s difficult to determine how one would react in such circumstances. Sometimes you face it head-on; other times, you try to avoid it. And there are also times when you simply freeze.

You neither feel the urge to do something about it nor the need to flee; you’re just… stuck.

To overcome the freeze response, you must first understand where this reaction is coming from and how the fight-flight-freeze response works.

You might be surprised to find out that “freezing” is more common than you think.

Understanding the Fight-Flight-Freeze Response

The fight-flight-freeze response is one of the fundamental mechanisms that have ensured our survival as a species.

Whenever danger was lurking in the bushes, our ancestors would rely on this automatic response to cope with whatever was threatening their survival.

Based on a quick, almost unconscious evaluation of the potential threat, our ancestors could choose the appropriate response.

This coping mechanism was so critical that it has been coded in our genes and passed on from generation to generation.

Furthermore, humans are not the only species that rely on this survival mechanism. All mammals seem to share the fight-flight-freeze response.

Throughout our evolution, the threats that we’ve been facing have changed dramatically. Nowadays, we have real dangers (e.g., an oncoming car) and perceived dangers (e.g., someone who disagrees with us).

Even though our world has reached a breathtaking complexity, the underlying mechanisms that drive your fight-flight-freeze response are pretty much the same as they were millennia ago.

If you wish to overcome the freeze response, you have to start by understanding its biology.

A wide range of physiological and psychological changes occur every time you encounter a stressful or potentially threatening situation.

Keep in mind there are no right or wrong ways to respond to potentially threatening situations.

Sometimes you ‘fight’, other times you run away.

Sometimes you ‘freeze,’ other times you might even faint.

It’s challenging to determine exactly how one will react to danger, regardless of whether it’s real or perceived.

What Happens in the Body?

The first physiological structure that activates when you’re faced with a potential threat is the amygdala, the part of your brain responsible for processing emotions such as fear or anger.

Under the influence of fear, your amygdala will signal the hypothalamus, which, in turn, activates the autonomic nervous system (comprised of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system).

As soon as the autonomic nervous system receives signals from the hypothalamus, your adrenal glands will begin to secrete cortisol and adrenaline.

These hormones will trigger a wide range of physiological changes, from accelerated heart rate and rapid breathing to increased peripheral vision, sweating, and muscle tension.

While the sympathetic nervous system oversees the fight-or-flight response, the parasympathetic nervous system regulates freezing.

One of the main differences between fight-or-flight and freeze is that your heart rate remains relatively stable during freezing, as if you were calm and relaxed.

It’s one of the reasons why some experts believe that freezing offers both humans and animals some extra time to process the situation and determine the best course of action. [1]

What happens in the Mind?

From a psychological perspective, the fight-flight-freeze response is the consequence of perceived fear.

Objectively speaking, the situation might or might not be threatening. What matters most is how you perceive it.

For some of us, speaking in front of an audience can trigger the same emotions as being locked inside a cage with a bear.

In other words, each of us develops conditioned fears in the sense that we learn to feel threatened by certain situations. For instance, a car accident can condition you to perceive driving as dangerous.

Long story short, whenever you encounter a situation that you label as “threatening,” your mind (and body) will act as if you are facing a real danger.

So in a way, we are the architects of our fears and phobias.

Here’s What Happens When You ‘Freeze’

Sometimes, an event may unfold so fast that you don’t even have the time to figure out if what you’re dealing with is a real danger or a conditioned fear.

One minute you’re walking down the street, the next minute you hear tires screeching, and without even realizing it, your whole body is in full alert.

By the time you realize that you’re out of harm’s way, your body has already entered the fight-flight-freeze mode.

Depending on the nature of the situation and how you usually respond to unexpected changes or potential dangers, fear may prompt you to act, run away, or freeze.

When you ‘freeze,’ the first thing you might notice is that time slows down, like you’re watching a video in slow-mo.

Even though you’re feeling anxious, your heart rate is relatively normal, and your breathing becomes shallow.

When in ‘freeze’ mode, your peripheral vision increases [2], allowing you to gain a better sense of your surroundings. That way, you can gain more information about what goes on around you.

Furthermore, some experts believe the freeze response is a form of dissociation that separates you from a potentially threatening situation, thus making it seem less dangerous. [3]

Finally, current research suggests that animals take advantage of freezing to scan their environment and decide how to approach a potential threat.

However, there’s a difference between animals and humans when it comes to freezing. In other words, while animals are “able to restore their standard mode of functioning once the danger is past, humans often are not, and they may find themselves locked into the same, recurring pattern of response tied in with the original danger or trauma.” [4]

Considering all this evidence, we could argue that freezing has its advantages as it allows us to gather more details and assess the situation before taking any further actions.

Is ‘Freezing’ the Sign of a More Serious Problem?

Up until now, we’ve established that ‘freezing’ can be an effective defense mechanism that creates mental space whenever we encounter a situation that we’re not quite sure how to handle.

But what if this response is overactive?

What if we tend to freeze in situations that are obviously not threatening?

Or what if it lasts too long and prevents us from making decisions or acting?

In such cases, an overactive freeze response may indicate the presence of an underlying condition.

Acute Stress

Acute stress is the first thing that pops into my head whenever I hear someone complaining about feeling ‘stuck’ or unable to decide.

When you spend most of your waking hours under stress – caused by work, personal problems, relationship issues – your body is in a constant state of arousal.

Your cortisol levels are up, you’re hypervigilant, and you behave as if everything is urgent and important.

Long story short, you’re in fight-or-flight mode.

That means every unexpected change that may occur in your environment will be automatically labeled as a potential threat.

But since being in flight-or-flight mode most of the day is incredibly draining, there’s a good chance you might stumble into situations where you simply don’t have the energy to react.

And so… you freeze.

As you can probably imagine, managing stress (if that is, in fact, the underlying problem) can help you overcome the freeze response.

Anxiety

Another explanation for why you tend to freeze whenever you’re dealing with stressful situations or unexpected events is anxiety.

And I’m not just talking about the fears and anxieties that you gain from unpleasant experiences.

I’m talking about anxiety as a personality trait.

For some reason, your brain is more sensitive to danger and prone to focus on negative scenarios.

In other words, you tend to take a relatively insignificant event and turn it into a catastrophe.

Current evidence suggests that, even though people with anxiety are more likely to flee from danger, they also tend to ‘freeze’ (tonic immobility) when faced with potential threats. [5]

Often, you might not even realize how easy it is for you to slip into catastrophic scenarios and imagine the worst possible ways in which a minor hiccup can unfold.

Long story short, an anxious mind is a mind that might freeze if pressures are high and circumstances urge you to make a quick decision.

But as in the case of stress, anxiety is a manageable condition.

Traumatic Experiences

In essence, trauma occurs when we’re faced with a situation or event which threatens our physical or psychological well-being.

I’m talking about major events that exceed our coping abilities, generating emotional overwhelm and feelings of helplessness.

Some of the most common events that can cause trauma are: car accidents, natural disasters, abuse (physical, sexual, emotional), loss of loved ones, invasive medical procedures, and neglect.

Given their tremendous emotional impact, traumatic experiences will always leave a mark, a reminder to stay vigilant and avoid situations that may cause the same pain and suffering you initially experienced.

It’s like having an oversensitive alarm that goes off and puts you in fight-flight-freeze mode whenever you encounter something that vaguely reminds you of the initial trauma.

In the context of trauma, mental health professionals believe ‘freezing’ is a sign of post-traumatic stress.

If that’s the case, the best thing you can do is consult a professional who can help you process your painful past and achieve post-traumatic growth.

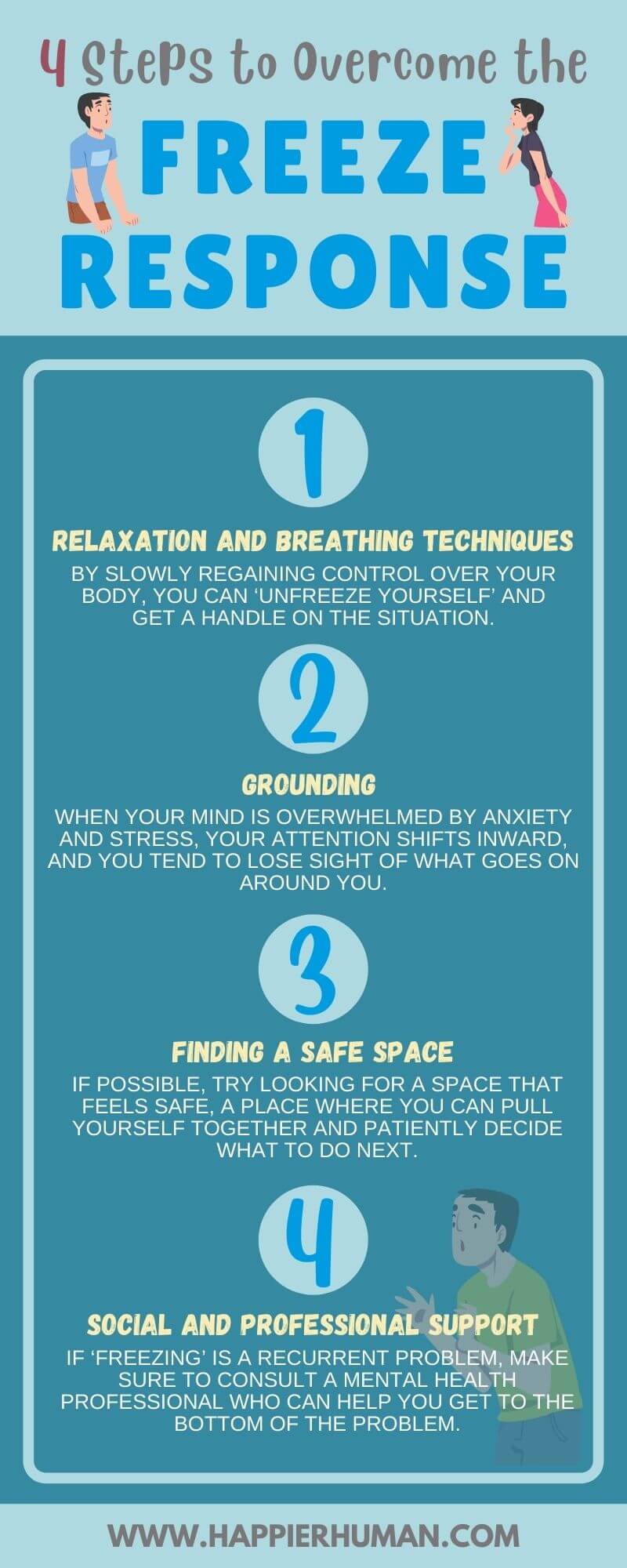

4 Steps to Overcome the Freeze Response:

Given that the fight-flight-freeze response is mostly automatic and deeply rooted in our biology, exercising complete control over how you respond to threats (real or perceived) can be pretty challenging.

In other words, there’s no way to anticipate how you’ll react to an unexpected (and possibly adverse) change in your environment.

However, the better you manage anxiety and stress, the less likely you are to ‘freeze’ in the face of danger.

Here’s how you can achieve that.

1. Relaxation and Breathing Techniques

Some of the most accessible tools for managing anxiety and overcoming the freeze response are relaxation and breathing techniques.

For starters, the mere act of shifting your attention towards your breath gets you out of your head and away from all the uncertainty and second-guessing that’s keeping you ‘frozen.’

Furthermore, breathing techniques are an excellent way to regain control over your body.

By slowly regaining control over your body, you can ‘unfreeze yourself’ and get a handle on the situation.

One exercise that’s both quick and easy to practice is deep breathing.

Here’s how you do it:

But don’t just save these exercises for when you’re feeling stuck.

Practice regularly so that when the freeze response kicks in, your mind already knows how to overcome it.

2. Grounding

Grounding is another helpful practice for when anxiety is so intense that it paralyzes you.

Just as breathing exercises help you get out of your head, grounding exercises allow you to escape the overwhelming torrent of thoughts racing through your head during a tense situation.

In essence, grounding is all about reconnecting with your surroundings.

When your mind is overwhelmed by anxiety and stress, your attention shifts inward, and you tend to lose sight of what goes on around you.

Using your senses, you can ground yourself in the present moment, thus shifting your focus towards the situation requiring a prompt response or a quick decision.

If you want to learn how to practice grounding, here are 20 examples to get you started.

3. Finding a Safe Space

Sometimes, just because a situation ‘feels’ urgent or threatening doesn’t mean you have to act on the spot.

Keep in mind that your fight-flight-freeze response might be overactive due to the stress and anxiety that have been weighing heavily on your shoulders for quite some time.

If possible, try looking for a space that feels safe, a place where you can pull yourself together and patiently decide what to do next.

Perhaps somewhere outside, somewhere quiet, and less crowded.

Or maybe you prefer an empty room where you feel safely separated from the situation or person that’s making you feel panicked and ‘stuck.’

4. Social and Professional Support

For some of us, being in the presence of others – usually, people whom we trust – can be comforting enough to overcome ‘freezing’ and plan our next step.

Sometimes, even a supportive and reassuring text from someone you hold dear can give you the courage to overcome mental blocks and manage difficult situations.

Even though texting a friend or seeking the presence of someone you feel comfortable around is soothing enough to get you ‘unstuck,’ I wouldn’t recommend using this solution constantly and indefinitely.

In other words, turning to others every time you ‘freeze; in the face of an urgent and tense situation will only prolong your underlying problem.

On top of that, others might not feel comfortable being your ‘safety net.’

If ‘freezing’ is a recurrent problem, make sure to consult a mental health professional who can help you get to the bottom of the problem.

Final Thoughts on Overcoming the Freeze Response

The fight-flight-freeze response is an essential defense mechanism that helps us navigate potential dangers, ensuring our physical and psychological well-being.

The problem with ‘freezing’ is that it sometimes keeps you from responding appropriately to a threatening situation.

In my opinion, it’s vital to understand where this reaction it’s coming from. Maybe it’s because you’re under too much stress and anxiety. Or perhaps the root cause is unprocessed trauma.

Aside from exploring the cause behind your constant ‘freezing,’ you can also:

Also, keep in mind that ‘freezing’ isn’t entirely wrong. Sometimes, the mind needs a few moments to assess the situation and develop an appropriate response to a potentially threatening situation.

Now, it's important to figure out if your freeze response relates to some sort of anxiety. If you feel like it might be, then you should understand what type of anxiety you're experiencing (this article will help) and also use the 3-3-3 rule to provide a quick relief when you have those anxious moments.

Finally, if you want to increase your happiness and life satisfaction, then watch this free video that details the 7-minute habit for planning your day to focus on what's important.

References

[1] K. Roelofs, “Freeze for action: neurobiological mechanisms in animal and human freezing,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, vol. 372, no. 1718, 2017.

[2] L. M. Gladwin, E. J. Hermans and E. J. Roelofs, “Freezing promotes perception of coarse visual features,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, vol. 144, no. 6, p. 1080–1088, 2015.

[3] A. Krause-Utz, R. Frost, D. Winter and B. M. Elzinga, “Dissociation and Alterations in Brain Function and Structure: Implications for Borderline Personality Disorder,” Current Psychiatry Reports, vol. 19, no. 1, 2017.

[4] K. Kozlowska, P. Walker, L. McLean and P. Carrive, “Fear and the Defense Cascade: Clinical Implications and Management,” Harvard Review of Psychiatry, vol. 23, no. 4, p. 263–287, 2015.

[5] N. B. Schmidt, A. Richey, M. J. Zvolensky and J. K. Maner, “Exploring human freeze responses to a threat stressor,” Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, vol. 39, no. 3, pp. 292-304, 2008.